FAQ

Questions from Professor Marjorie Chan's Presentation on Written Cantonese

Questions from the Registrants

Professor Chan has made her responses to the registrants’ questions available to anyone who is interested in viewing them. Please click here for the pdf file. The audio that accompanies the file is provided below.

Please click on Questions #5 and #16 for the resources suggested by 張老師 and her team.

- As far as I know, they aren’t, in large part because use of vernacular written

Taishanese or Zhongshanese is rare to (almost?) non existent. - If there are such materials online, I would love to know about them!

- I’m afraid I am not aware of such a book for Cantonese.

- But, if you read the comments in Amazon.com, there are pros and

cons in the approach that the author, ShaoLan Hsueh, had taken. - And lastly, the approach really isn’t new. Teachers often do something like this in

beginning Chinese courses in introducing Chinese characters as a mnemonic

device to help students learn and as a fun way to start being introduced to writing

Chinese characters.

- Hambaanglaang is a wonderful, colloquial Cantonese word that is used in everyday, colloquial speech. If one is writing down precisely, verbatim, what one has said, then, by all means, use hambaanglaang , 冚唪呤 (and other orthographic variants).

![]()

- Regarding the website, https://hambaanglaang.hk/ hk/, founded in December 2019, a LOT of time and effort had been put into preparing materials and making them available online at their website to help in the learning of Cantonese: speaking, listening, reading, and writing. I will leave more discussion on this to the dedicated teachers connected with Cantonese Alliance.

- There are lots of apps or modules within language learning software programs that include stroke order, and these could be fun for students to look at and play with.

- Stroke order and direction of strokes go together. Having a good foundation on that, I think, is important.

- How much to emphasize … that is something for teachers to determine, in balancing between correct stroke order and maintaining students’ enthusiasm for learning the language. A delicate balancing act …

- Many of the attendees here who teach Cantonese — especially to elementary school children — would be better equipped to respond to this question! …

- At Ohio State University, our instructors teach conversational Cantonese to university students; as a result, our textbook choice differs greatly from

…

張老師 is sharing some links in Chat for everyone!

- San Francisco Unified School District: MeiZhou Chinese 美洲華語: http://www.mzchinese.net/

- In addition to MeiZhou, the Chinese immersion program at Alice Fong Yu Alternative School in San Francisco has added Sage Books’ Basic Chinese 500 基礎漢字 500: https://www.sagebookshk.com/product/basic-chinese-500/

- It’s critical to cultivate a love for reading

- Storybooks in Cantonese:

- Storybooks Canada with Dr. Dennis Amelunxen’s stroke order tool: https://chinvocab.com/sbca/

- Hambaanglaang.hk has published a lot of free downloadable storybooks in written Cantonese and has recently added many new resources such as conversations, comprehension exercises, and written Chinese: https://hambaanglaang.hk/

- Dr. Amelunxen has added the tool to some of the HBL stories https://cantonesealliance.org/r-and-w-stage-3/

- and proverbs: https://cantonesealliance.org/r-and-w-stage-4/

- Cantonese Reading Materials in text files compiled by Eric (Hulk): https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1sihq61nNqXJZFhkHCne9V_EFfFgnAU-K

- All of the text files work with the Cantonese Popup Dictionary: https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/cantonese-popup-dictionar/pjnbhojkojmibobcpfgihhnohboldhip?hl=en

- Make sure “Allow access to file URLs is checked for the dictionary.

- If you need support, please join our Discord server. Our volunteers can answer your questions: https://discord.gg/bXJj3SgxVb

- Greenwood Cantonese Reading Materials: https://www.green-woodpress.com/products_list.php?iscantonese=1

- Famous novels translated into written Cantonese (Little Prince and Animal Farm), which can be read with the Cantonese Popup Dictionary: https://www.cantonese.com.hk/?fbclid=IwAR1GAJI3jdWdUamj7krYd0_kcQtJjjZ3aZX_t7FOXqDMo-Qjp5yKkM__zyg

- Magazine about Cantonese culture in written Cantonese: https://resonate.hk/

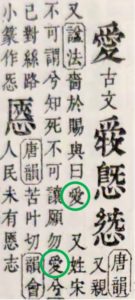

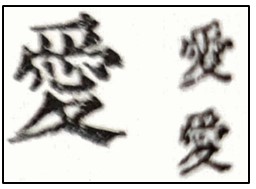

- Regarding the removal of the heart component, 心, from 愛 in the simplified form, 爱, this predates the 20th century script reform, which I addressed earlier as part of my presentation today.

- That the orthographic form without the heart component pre-dates the script reform of the 20th century can be seen in the 1716 Kangxi Dictionary (康熙字典), which is a useful source for orthographic variants that have been used over the centuries.

- (That may be somewhat like English dictionaries that provide two spellings, ‘plow’ and ‘plough’ for the same farm tool, but the English dictionaries also add information on the source of the spelling difference, one being American English and the other British English.)

- The terms “word” and “character”:

- Word: 詞 (詞典) Character: 字 (字典) – strictly the written form

- I think this might depend very much on individual Cantonese speakers in mainland China.

- The government does not encourage the use of characters that are non-standard. As a result, it takes special effort and interest for mainlanders to take time to be exposed to vernacular written Cantonese, and to use it himself/herself. Ditto for those in the Cantonese diaspora, be it North America, or Vietnam, or Malaysia.

- I notice, over the years, for example, the entertainment magazines distributed in Vancouver seem to have reduced the use of vernacular written Cantonese.

- I think the Web is an important place to “introduce” written Cantonese and other

vernacular forms for anyone browsing the internet. Take, for example, the link on the

Web provided below, which lets Cantonese speakers see how one might write Cantonese.

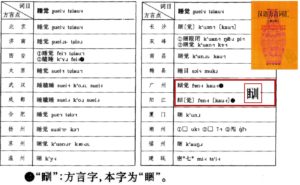

The link uses only those characters that are in standard Chinese, but the question that is posed is clearly intended to be read in Cantonese. Notice that in the video itself, the

vernacular graph for ‘sleep’ is used: 瞓. Thus, netizens are introduced to two graphic forms for this item: 訓 and 瞓.

- This is a huge topic that involves the history of the Chinese language, changes over time and distance, and which branch of the Chinese language was selected to serve as the standard spoken form on which the written is based.

- My own first exposure to written Cantonese were the lyrics in the old black-and-white Cantonese opera films produced in Hong Kong, as shown here. I went with my grandparents to watch the old films in the movie theaters in Vancouver Chinatown. The lyrics allow the audience to follow the singing.

無敵楊四郎

Line sung by 林家聲

1959 HK Film

- No, and that is because Cantonese is not used as some kind of written standard in education, government, etc.

- And even with standardization, there will still be non-standard graphic forms, for abbreviation, etc. The current existence of traditional and simplified characters adds an extra wrinkle to this.

- One thing interesting to watch over the years is to see which variant forms become more dominant in usage than some others: our choice of input methods (e.g., if you use Pinyin to write Cantonese, the vernacular characters would not appear so readily). We are influenced by different sources that make their own selection of orthographic forms – Google Voice Typing, etc.

- I think as long as people have fun expressing themselves in writing in Cantonese, I’m all for it!

- When one is writing very casually and colloquially on the internet, for example, part of the fun is being creative and just enjoying oneself. There is always a time and place for different types of activities.

- Someone who is a teacher teaching Cantonese, for example, may want to avoid introducing mixed scripts, and may choose to use only the forms introduced in the textbook, especially for younger learners.

- In Taiwan, in recent years the government has included the learning of one’s mother tongue. Taiwanese (S. Min), for example, is now taught in schools and, as a result, provides its set of standard characters. There are differences of opinion on choices of characters, a topic of interest to my advisee who wrote his thesis on it. (張老師 has a copy that she could give to those interested: Cockrum, Paul. 2022. Taiwanese Southern Min: Identity and Written Sociolinguistic Variation. OSU M.A. thesis.)

- With respect to vernacular writing in the mainland, the government discourages non-standard characters. As a result, efforts would be much more sporadic. Keep in mind that prior to the founding of the PRC, vernacular writing in various Chinese dialects have existed, such as the use of the Suzhou dialect in 馮夢龍’s (1574-1646) 山歌, the use of Chaozhou and Quanzhou (S. Min dialects) in the Ming dynasty opera script, 荔鏡記 (a.k.a. 陈三五娘).

- I think that one valuable activity for learning to read the vernacular written language is to read folk literature and seeing the words for nursery rhymes, lullabies, etc.

- As the adage goes, “Use it or lose it.” If no-one is interested, then the language will eventually disappear. Language vitality is an important issue that I address in my courses, especially in my “Chinese Dialects” course, but in my other Chinese linguistics courses as well.

- Hong Kong Cantonese and Guangdong Cantonese differ in numerous ways, a topic that would take time to elaborate. These include the sound system (e.g., the loss of the high-falling tone in the 陰平 tone in Hong Kong Cantonese, tone mergers that are taking place in Hong Kong), vocabulary (esp. in the greater code mixing in using English), etc.

The work of Chinese language teachers is so very important!

- 訓覺 is also written as 瞓覺, with 瞓 a vernacular Cantonese character, as I showed in Question #6. The etymon (本字) is 睏, but in Cantonese, that character is pronounced [kʰwɐn], and not [fɐn], as in the colloquial word for ‘to sleep’: [fɐn kau]. The selection of a phonetic loan, 訓, or the creation of a vernacular character, 瞓, presumably serves to avoid the problem of needing to know when to pronounce 睏 as [kʰwɐn] or as [fɐn]. (A comparable situation in English would be such words as ‘bow’ and ‘read’ that have multiple pronunciations, depending on context.)

- Re the question, I am not aware of such sources, but the 汉语方言词汇 (2nd edition, 1995) may be a helpful resource. It tries inform the reader of the original character (本字) when other graphic forms are found as well. But note that the written Cantonese character,

, is in the corresponding simplified form there.

, is in the corresponding simplified form there.

- If there is a trend, I would think it would be convergence, given the heavy push by the Chinese government for standard characters and the use of Putonghua. That is also true between the use of “standard Cantonese” and some more rural subvariety of Cantonese. For example, my paternal grandmother used 家下 while the rest of the family used 而家 ‘now.’ This can involve the gradual replacement of one form, one pattern, with another.

- The post-verbal use of 先 ‘before,’ for example, may eventually be replaced by pre-verbal placement. An interesting observation is that of pre- and post-verbal in some people’s speech. Is that part of the transition: pre-verbal 先 > pre- & post-verbal 先 > pre-verbal 先? The presence of pre- and post-verbal 先 is not a recent phenomenon. I heard it in 關德 興’s speech in the late 1950s when he played 武松 in a Cantonese opera film. I was surprised that it occurred well over half a century ago!

Our Cantonese language teachers in this group are the best sources for such suggestions and tips!

張老師 and her team have been doing a great job in making more resources and teaching materials available that are shared among the teachers!

Check out 張老師’s advice and online resources in Chat!

- Encourage reading

- Pick reading materials that are meaningful and relevant to the learners

- Start out with materials in written Cantonese so that what the learner reads is consistent with the spoken language (please see my references in #5)

- Fun games and apps, for example:

- Maomi Stars: https://maomistars.com/

- Turtle Learn: https://en.turtlelearn.com/

- Use Cantonese keyboards:https://jyutping.org/keyboard/

- I’m developing a program in reading and writing

- Write diary and join Cantonese group to practice writing Cantonese (e.g., the Cantonese Alliance Discord Server)

- Encourage creative writing and writing with a group of friends

- I’ve written about how to teach children to read and write. Please go to the section “How to teach children Cantonese in overseas communities,” then “What is a good age to start teaching reading and writing? What are the best practices?”: https://cantonesealliance.org/faq/

- I think it is important to keep in mind what are one’s highest priorities for different purposes and at different levels.

- At the right level, students interested in digging deeper into the writing system of Chinese in general, and vernacular written language, can be encouraged to explore some etymons (本字).

- This is a time period of almost half a century across three different communities … I will pass on this for this occasion where my talk focusses on written Cantonese!

- One difference between Hong Kong and Guangzhou Cantonese that I mentioned earlier is the loss of the high-falling tone for 陰平 tone. Another example, from segmental phonology, might be the loss of labialization of velar stops before [ɔ], as in the loss of contrast between 剛 and 光, 講 and 廣, 各 and 國, etc.

- I think Guangzhou Cantonese speakers are likely to, consciously or unconsciously, adopt more standard Chinese (Putonghua) patterns into their spoken Cantonese. For example, I have a feeling Guangzhou Cantonese speakers may use 嗎 as a question marker, whereas traditionally Cantonese does not do so. Mind you, that may also be changing in Hong Kong as well. Do Cantonese speakers today say, 你好嗎? Or not use that at all, or maybe sometimes opt for: 你好呀嘛? (or 你好丫嘛?) ?

- This is a very big topic, even if limited it to vernacular writing …

- I touched upon this topic briefly in my presentation, with the ‘to sleep’ example from the page in the 汉语方言词汇 (2nd edition, 1995), a valuable source, albeit several decades old now, for comparisons across the major regional varieties (方言) of Chinese.

- Let’s focus on the word ‘to sleep’ across Chinese dialects that was mentioned earlier, one choice that does not show up explicitly in the 汉语方言词汇 is 寐, whereas both 睡 and 睏 do. Zhongshan (中山) dialect’s word for it is [mi] 寐. The graphic form, 寐, is in the 珠江三角洲方言詞匯對照 (A Survey of Dialects in the Pearl River Delta). 1988. Vol. 2. Comparative Lexicon. Zhongshan (Shiqi 石歧) is the only Yue dialect among the 25 Yue dialect sites in the survey to use 寐 for ‘to sleep.’ Longdu (隆都, E. Min), spoken in Zhongshan district, is the only other dialect in the survey that uses 寐.

- 寐 is potentially the etymon in 建甌 (N. Min), where it shows up in the 汉语 方言词汇 with phonetic loan characters, “密七”, pronounced [mi tsʰi]. Zhongshan (Shiqi 石歧) has likely borrowed the word from Longdu …

- I think that, if the goal is to encourage and support the use of written Cantonese, whatever helps to increase folks’ interest and enthusiasm in writing down what they say, I am all for it.

- Hongkongers — and increasingly, mainland youth as well — do a lot of code mixing, so for that to show up in their writing on the internet should be very natural. Precisely, that is how they talk. Writing down verbatim their speech is what is the slogan, 我手寫我口, is all about!

- I think the choice of sentence-final particle (SFP) begins with what is the spoken form used by the speaker, and then determining the written form, which may have one or more orthographic variants. The choice is then up to the individual or, if this is in a course, then what the teacher uses in the class.

- In the Cantonese course that we teach at Ohio State University, the focus is on conversational Cantonese, so we don’t worry about what precise orthographic form might get chosen by the students. The textbook, of course, has its choices in the character portion of the textbook.

- These are very valid questions. The first two are actually general questions, and are precisely what Cantonese Alliance aims to do: find ways to promote Cantonese with help from members who can volunteer to help create and provide resources for the study of the Cantonese language, both spoken and written, as well as introduce various aspects of Cantonese culture, be it cuisine, learning about the old Chinatowns set up by early Cantonese immigrants, etc., as some of the various means to promote Cantonese.

Re #1: Do join the Cantonese Alliance Discord Server: https://discord.gg/bXJj3SgxVb

Re #2: Please check out the Cantonese Alliance websites:

- https://cantonese-alliance.github.io/language.html

- https://cantonesealliance.org/

Re #3, I think this is where, if the venue is something very casual, then any method to write down what the speaker has in mind will be helpful, even if it involves, say, using some self-designed romanization, selecting a character that has the same sound as the target word (despite knowing that it really shouldn’t be that word – that is, the use of phonetic loan), or inserting an English word, etc., to help complete the sentence that is primarily written in Cantonese; that is, the sentence is intended to be read in Cantonese.

The goal is to communicate in Cantonese, using what resources one has. In some ways it is no different from learners of Mandarin Chinese putting down Pinyin when they don’t know how to write the Chinese character(s). And their Pinyin may be spelled a bit wrong … Or they may insert an English word when they don’t know the Chinese term. That’s far better than a blank space!

- I don’t think so. I think the most that tech companies can do would be to popularize the use of certain graphs. Standardizing a set of graphs for writing Cantonese is a daunting task. There may be certain graphic forms that are more commonly used than others, due to input methods, fonts, apps, etc., etc. The more often some particular form is seen — and if they are easily accessed using whatever devices or apps that one has — that may be what will help to determine the most frequently chosen orthographic forms. But that is not standardization per se.

- Even governments setting standards don’t necessarily result in everyone abiding by those standards, especially for casual, informal writing. Even if some orthographic variants are chosen to be the “standard” forms, there could still be informal, “non-standard” (俗體) variants that may be used by the populace, not to mention the additional complication of the existence of traditional and simplified Chinese characters currently in circulation.

- At the same time, the more rigidly one insists on standards, the less fun people will have in writing the vernacular language, and the goal of promoting the use of vernacular Cantonese writing might be that much more difficult to achieve.

Selected questions submitted to the Zoom chat box during the presentation

As Miss Kini noted, 近 uses Tone 5 for the adjective. In compounds, 近 is typically pronounced with the literary pronunciation using Tone 6, which is not surprising, since these compounds are connected with standard Chinese. Only the colloquial usage as a simple adjective, or monosyllabic verb (with or without aspect marking) has preserved the 陽上 tone (Historical change: 陽上歸去 (Tone 5 > Tone 6).

I’m positive Cantonese use of the characters, 雲吞, is a case of phonetic loan … It would be interesting to know when the Cantonese decided that they prefer the characters, 雲吞, which everyone can read, but not everyone would know how to read the characters, 餛 and 飩, in Cantonese. So, the choice of 雲吞 is very likely for easy readability of the Cantonese populace, and never mind stuffy etymons (本字)!

My 古漢語大詞典 in my Pleco app gives the following. (I replaced the simplified form of 餫 with the traditional form, as the simplified form doesn’t show up here, and actually not sure why Pleco has GH showing the simplified form …)

GH in Pleco:

一種麵食。亦作“餫飩”。用很薄的面片包餡做成,形如耳朵。廣東

How to use the materials on this website

If you’re a beginner, the best place to start is Brittany’s videos for beginning learners. The songs on the Cantopop page come with vocabulary lists. Brittany’s video clips provide subtitles in Cantonese, Romanization, and English. I’ll be adding resources for beginners.

The movies will expose you to Cantonese culture, but the language is challenging without a tutor. I’ll be adding vocabulary lists on Quizlet to go with the movies so that beginners can learn a small set of key vocabulary for each of the movies presented here.

I usually wait until my students have about 30 to 40 hours of formal instruction before I introduce movies. Little Big Master is a good movie to start. The language is relatively easy since the movie is about a principal and 5 little kids. The next movie I’d recommend is Still Human. Some English is spoken in the movie, and the plot is relatively straightforward but very moving. Both movies introduce you to social issues such as poverty and racial prejudice in Hong Kong.

If you have acquired slightly more grammatical structures (e.g., complex sentences) and the vocabulary for a large variety of topics, you’ll be able to follow the songs and Brittany’s video clips, especially with full transcripts and subtitles. If you can only understand a small fraction of a movie, please do not worry. My students who make the fastest progress are usually the ones who watch a lot of movies, videos, and TV dramas. It’ll be very helpful to you if you follow the movie handouts.

By advanced learners, we mean learners who can sustain a conversation in Cantonese and who can tell short stories and describe people and places briefly. If you fit this description, you’re ready to relax and enjoy any Cantonese movies, videos, and songs. Don’t worry too much about how much you can understand when you watch a movie. My handouts will be guiding you so that you can learn about Cantonese culture and acquire new vocabulary and grammatical structures. Some of the handouts have transcripts of specific scenes so that you can take a closer look at the language and the intended messages. It’s better to start with movies with modern, realistic themes, e.g., Little Big Master, A Simple Life, Still Human, and Zero to Hero. Ancient history dramas and Stephen Chow’s comedies are actually not easy to understand. The former tends to use more classical Chinese and the latter requires a good grasp of cultural references.

Here’s a curriculum that I have designed. Please feel free to contact me if you want to discuss it or if you have any questions: dennig@gmail.com, lcheung2@stanford.edu

Children can learn a surprising amount about Cantonese culture by watching movies. I’ll share my experience with my son. He used to sit with me when I was watching the Cantonese movies that I’d be teaching in class. Before I knew it, he had removed the string from his favorite bow and taped it to the back of his head. At age 4, he was imitating Jet Li’s Wong Fai Hung 🙂 In elementary school, he did a project about Bruce Lee. There were further examples. Recently, he surprised me by asking me to host a Cantonese movie night for his college friends. They’re learning about each other’s heritage cultures, and my son thinks Hong Kong movies provide a good introduction to Cantonese culture. Unfortunately, some of these movies have violent scenes. I’d suggest that parents watch the movies with their young children and skip those scenes. Even better, pick movies that are age-appropriate 🙂

Most commonly asked questions about Cantonese

Among my students who are heritage language speakers, being able to communicate with their grandparents is often cited initially as the #1 reason for why they want to learn Cantonese. Many of them were watched by their grandparents before they started attending preschool or kindergarten. They lament not being able to talk with their grandparents beyond very simple exchanges. As they learn more Cantonese, many feel empowered to embrace their heritage as they form deeper connections with their parents and the Cantonese community.

An increasing number of Mandarin speakers has shown up in Cantonese classes over the last decade or so. Very often, they talk about their interest in Cantonese popular culture. They’re excited that they can understand more when watching Hong Kong movies or TV dramas in Cantonese, and they want to improve their Cantonese pronunciation when they sing karaoke with their friends.

A third group of individuals learn Cantonese for their jobs. They can be future or current medical professionals, teachers, lawyers, judges, police officers, or any other individuals that need to interact with Cantonese speakers in communities with a high concentration of Cantonese speakers. There are some who want to work in Hong Kong. Though they can survive by speaking English in their offices, they prefer to interact with locals so that they can experience real Hong Kong.

There are always learners who are simply intrigued by Cantonese – its rich tonal system, lively vocabulary, preservation of classical Chinese as well as linguistic features of the minority Jong language (壯語), which formed the substrate of the Cantonese language in its evolution.

Unfortunately, the answer is “no.” Please read this 2019 article for details.

Mandarin speakers who have not been exposed to Cantonese before will not be able to understand Cantonese. The same holds true for the other way round. In linguistics, we say Mandarin and Cantonese are not mutually intelligible.

That depends on your goal. If you’re a heritage language speaker, I’d suggest that you learn your heritage language first, be it Mandarin or Cantonese. It’ll allow you to feel connected to your family and your heritage community. Though Mandarin and Cantonese are not mutually intelligible, being proficient in one will help you to learn the other.

This question has caused a lot of confusion mainly because the English word “dialect” carries negative connotation. It’s therefore better to use a Chinese expression that has existed for over 2,000 years – fōng-yìhn (方言) “regional languages.” An ancient book by this title was published over two thousand years ago. Before the Qin Dynasty, emperors sent officials out every August to collect language samples and then organized them. Currently, the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China recognizes 10 fōng-yìhn. Mandarin is one of them and Cantonese is another one; that is, they are at the same level. Within each fōng-yìhn are sub-categories, e.g., Sei-yāp pin (四邑片) and Gwóng-fú pin (廣府片) in the Cantonese fōng-yìhn. Each sub-category consists of many varieties, e.g., Tòih-sāan-wá (台山話) in the Sei-yāp pin (四邑片) and Gwōng-jāu-wá (廣州話) in the Gwóng-fú pin (廣府片).

If you’re interested in learning about the history of how one fōng-yìhn became the national language of China, please read Dr. Gina Tam’s The Invention of Chinese.

This is a sad question. Hong Kong has been considered the capital of Cantonese language and culture. Unfortunately, some have predicted the demise of the language in the next couple of generations if nothing is done to stop that trend in Hong Kong. However, the tide seems to have turned in the Cantonese Diaspora since around the mid 2010s. New immigrants from Hong Kong are more aware that language is tied to identity. They are more likely to want their children to learn Cantonese. At the same time, many in the generation born to immigrant parents are passionate about passing their heritage language and culture to their children, evidenced by the grassroots efforts to produce relevant Cantonese learning materials and put them on the Internet. This is what the Cantonese Alliance of North America is trying to accomplish: Connect Cantonese instructors and organizations to preserve and promote the Cantonese language.

The most effective way to learn grammar is to learn it in context. I teach haih (係) “to be,” yáuh (有) ” to have,” and móuh (冇) “not to have” in my first lesson when I teach my beginning students how to introduce themselves – who they are and what family members they have. I wait until students have a little bit of exposure to noun phrases in Cantonese before I introduce the linker ge (嘅) as in ngóh ge hohk-sāang (我嘅學生) “my student(s)” and classifiers such as go (個) and dī (啲). It’ll be easy for me to explain why Cantonese speakers prefer classifiers when we are talking about possessives. Classifiers make it clear whether we’re talking about singular or plural nouns; e.g., ngóh go hohk-sāang (我個學生) “my student” vs. ngóh dī hohk-sāang (我啲學生) “my students.” Another example is the grammatical structure jēung (將). This highlights the grammatical object by moving it to a preverbal position; e.g., jēung tìuh yú fong-yahp go wohk léuih-bihn (將條魚放入個鑊裏面) ‘jēung + the fish + put + inside + the wok’. The best way to teach and practice this structure is through teaching simple recipes.

Yes. Written Cantonese appeared in different genres of Cantonese songs very early on. The first known work is dated 1713. Though written Cantonese was very much part of Cantonese culture, children did not grow up learning it in Hong Kong during the colonial rule. This has persisted after the turn-over of Hong Kong to China. As a result, Cantonese speakers have invented modern-day Cantonese characters. Take the first four characters of this website’s title as an example: 佗佗佻佻 “in a relaxing manner” are in traditional written Cantonese. The modern-day version is 他他條條, which are common characters with the same pronunciation: tā-tā tìuh-tìuh/ta1 ta1 tiu4 tiu4.

In recent years, there have been efforts to popularize written Cantonese. The inaugural issue of Resonate (迴響), a Cantonese literature periodical, was published in July 2020. The nonprofit organization Hambaanglaang (冚唪唥) has been publishing storybooks in written Cantonese for child and adult learners since 2021, and the books have Jyutping and English translation. You can download free texts, audios, and videos from its website: https://hambaanglaang.hk/.

How to teach children Cantonese in overseas communities

The short answer is “no.”

It’s important to recognize that there are individual differences in language acquisition, be it first, bilingual, or multilingual language acquisition. One of the significant contributors to individual variation is the quantity and quality of the language that children hear. Speaking to children often and very early on is critical. Babies are developing their abilities to identify and distinguish the speech sounds crucial in their speech communities in the first 10 months of their lives. They’re also developing other skills that are important for language development, e.g., imitation of turn-taking.

Inserting words from one language into the grammar of another language (code-mixing) or switching from one language to another (code-switching) are normal in multilingual communities. However, I’d encourage parents to separate their languages when the child is very young. I adopted the one-parent-one-language strategy when my son was born. By the time he was 1;9, I had definitive proof that he had separated the two languages by listening to how he pronounced the final consonants -p, -t, and -k in Cantonese vs. in English. In Cantonese, -p, -t, and -k are not released regardless of the phonological environments they appear in; e.g., -k is pronounced like the English -k in “don’t kick the door.” By contrast, how -p, -t, and -k are pronounced in English is affected by their phonological environments. For example, while it is not released in “don’t kick the door,” it is when it appears at the end of an utterance; e.g., “give me a kick.”

There are lots of wonderful resources for children on the Internet. Here’s a small sample:

- Most children respond well to music. Rhythm “N” Rhyme, is a music program that focuses on Cantonese language and music development for young children. Locy Lee Learning teaches Cantonese through music. It provides classes for children aged 0 to 8. 閱讀粵正Cantonese Literacy has a collection of short songs on YouTube with Jyutping and Chinese characters.

- Hey Mommio has short videos on a wide range of topics, e.g., stories, parenting hacks, recipes for toddlers, and fun interactions between the host and her child. The videos come with Jyutping, Cantonese characters, and English translation.

- Little Explorers Cantonese offers resource packs, each consisting of 24 videos that engage children in fun activities while teaching vocabulary and writing.

- Cantonese Mommy offers lots of fun activities and ideas for young children to learn Cantonese.

- Cantonese for Families 屋企講廣東話 provides parents and learners with a lot of interesting Cantonese learning material for kids and adults. In addition, they have an active FB page.

- If your child likes to draw, roundbunny is a good site for you. The host teaches children how to draw in Cantonese. She also has videos about parenting and really cute ones showing her young child reading classical poems.

- Twin Voices Chinese School on Facebook has some of the cutest and most timely vocabulary cards for young learners, e.g., key words from the animated movie “Turning Red.”

- Uncle Calvin 廣東話教室 has over 50 fun videos with English subtitles for children aged 0-5.

- If you want to purchase bilingual children’s books and other learning materials, Little Kozzi has a lot to offer.

Maximizing Cantonese input is crucial since Cantonese is a minority language which is not supported by the larger society. It’s recommended that parents speak Cantonese to their children as soon as they are born. Some parents choose to speak Cantonese exclusively to them until they start preschool or kindergarten. It’s also very helpful for adults to narrate everything that they and the children are doing; it’s like a radio host broadcasting ongoing activities to an audience. Scaffolding is another skill that has been studied in child language research; e.g., Child: Doggie; Parent: That’s a nice doggie. He’s wagging his tail. Reading is also a fun and enriching activity. The earlier we read to our children, the more natural it will be when it comes time to teach our children how to read and write.

Furthermore, we can teach little kids Cantonese through music, arts, sports, visiting grandparents and other relatives, and having playgroups with other Cantonese families and children so that our children feel that it’s normal to speak Cantonese. Cantonese Mommy has a personal story to share about how she teaches her child multiple languages including American sign language. Here’s a discussion about the one-parent-one-language strategy on Cantonese Mommy.

The consensus among parents is to start reading books to children as early as possible — board books, picture books, and books with illustrations. Gradually, children will associate words with sound and meaning. More and more authors have been writing Cantonese storybooks for children; for example, Serena Li of Duck Duck Books has been publishing children’s books that cultivate emotional intelligence; Katrina Liu has started converting her colorful Mandarin bilingual books for young children into Cantonese; Deborah Lau has published two children’s books in written Cantonese and Jyutping with English translation.

Children build confidence and fluency in reading through their mother tongues. Parents interested in teaching their children how to read and write in Cantonese are very lucky. Hambaanglaang started producing storybooks in written Cantonese and Jyutping in 2021. The stories are fun and the level of written Cantonese is graded from beginning to advanced. The storybooks can be downloaded for free from their website, and each is supported by an audio and a video file. In addition, Jyutping is presented on the musical staff to show the ups and downs of the Cantonese tones.

If parents are wondering when they should introduce reading in standard Chinese. Luckily, at the end of each of hambaanglaang’s printed storybooks is a version of the same story in standard Chinese. Initially, parents can read this to their children casually. Children are quick to pick up the correspondences between a Cantonese expression and its equivalent in standard Chinese, e.g., the verb to be is 係 haih in Cantonese but 是 si in standard Chinese. When they start noticing these correspondences, parents can start teaching standard Chinese in a more structured manner. A mother has documented her journey in a video from her channel roundbunny.

What about writing? “How we practice writing Chinese at home without using any worksheets” talks about fun things you can do to introduce writing to your children.

Dr. Dennis Amelunxen has invented a stroke order tool, which he has incorporated in the Cantonese stories from Storybooks Canada. He has started to incorporate the tool in hambaanglaang stories and proverbs. Being able to see the stroke order makes it so much easier for anyone to learn writing characters. We can add the tool to our own list of characters on his website.

What has been helping is not to put too much pressure on ourselves and our children. We can follow their lead. Based on their interests, we then create games/activities for them to learn Cantonese. Since many kids love music, that’s a natural motivation for them to sing some Cantonese music including Cantopop. Joining online Zoom sessions helps; they can see many other kids are speaking Cantonese, too. It is not just a mommy or daddy language.

Apps for learning reading and writing

Resources for adult learners

This podcast hosted by veteran Cantonese instructor Raymond Pai and advanced learner Cameron White covers topics that are important and interesting to Cantonese learners, e.g., mood words that appear at the end of an utterance, commonly known as sentence-final particles. Each episode provides a vocabulary list and a transcript in Jyutping, characters, and English translation.

Language Kaleidoscope 語言萬花筒; also available on Spotify.

This podcast hosted by two renowned Cantonese linguists Stephen Matthews and Virginia Yip covers fascinating linguistic phenomena in Cantonese, e.g., whether Cantonese has a 7th tone.

粵語長片台 offers 261 Cantonese feature films from the 1950s and the 1960s and 3 from 1970 on YouTube, as of today (4/4/2022). Among the notable older films are Bruce Lee’s A Myriad Homes 千萬人家 (1953) and The Thunderstorm 雷雨 (1957). In just a little more than 7 months, 粵語長片台 has attracted over 11 M views.

8號電影院 – 美亞 & TVB (Hong Kong Movie Channel) has over 60 newer Hong Kong Cantonese movies in different genres, e.g., action, horror, comedy, and romance.

If you search “Hong Kong movies with English subtitles full movie” on Youtube, a long list of films will appear.

Black Lives Matter Cantonese has a channel on Instagram that teaches the vocabulary for talking about this movement.

Dim Sum Saying is a channel on YouTube that provides Cantonese flashcard videos. Its tongue twister videos are funny. What’s most special is its series that consists of common Cantonese expressions (e.g., 對唔住 deui-`mh-jyuh “sorry” and 梗係 gán-haih “of course”). Each expression in this series is illustrated by clips from multiple movies.

jyut6toi4粵台 | Learn Cantonese is a channel on Instagram teaches Cantonese slang and colloquial proverbs such as 扮哂蟹 baahn saai háaih “to feign” and 吹水 chēui-séui “to bluff.” If you’re interested in learning colloquial Cantonese proverbs, Cantonese Proverbs in One Picture is an excellent site for you. Though they are not flashcards, there are over 80 proverbs, each of which is supported by written Cantonese, Yale Romanization, English translation, and a recording in Cantonese.

As of today (4/4/2022), I have made close to 70 sets of flashcards on Quizlet to support my Cantonese classes, and more will be coming. You’ll be able to hear how each expression is pronounced while reading Cantonese characters, Yale Romanization, and English translation.

Dialect Classrooms‘ mission is “to save dialects by learning dialects.” It offers classes in over 20 dialects or regional languages, and Cantonese is one of them.

Learn Jyutping provides excellent lessons on Jyutping, a Cantonese Romanization system developed by the Linguistic Society of Hong Kong in the 1990s. This system uses a number system to represent tones, which may not be intuitive initially. However, once you’re used to it, you’ll find it easy to type tones.

Cantonese with Brittany has accumulated a large number of videos across a wide range of topics, in addition to the ones on the “Learning Cantonese through Videos” page of the current website. The host is lively and her topics are always relevant in the North America context.

InspirLang offers fun videos and classes for learning Cantonese. The host has recently started to create videos for learning Taishanese.